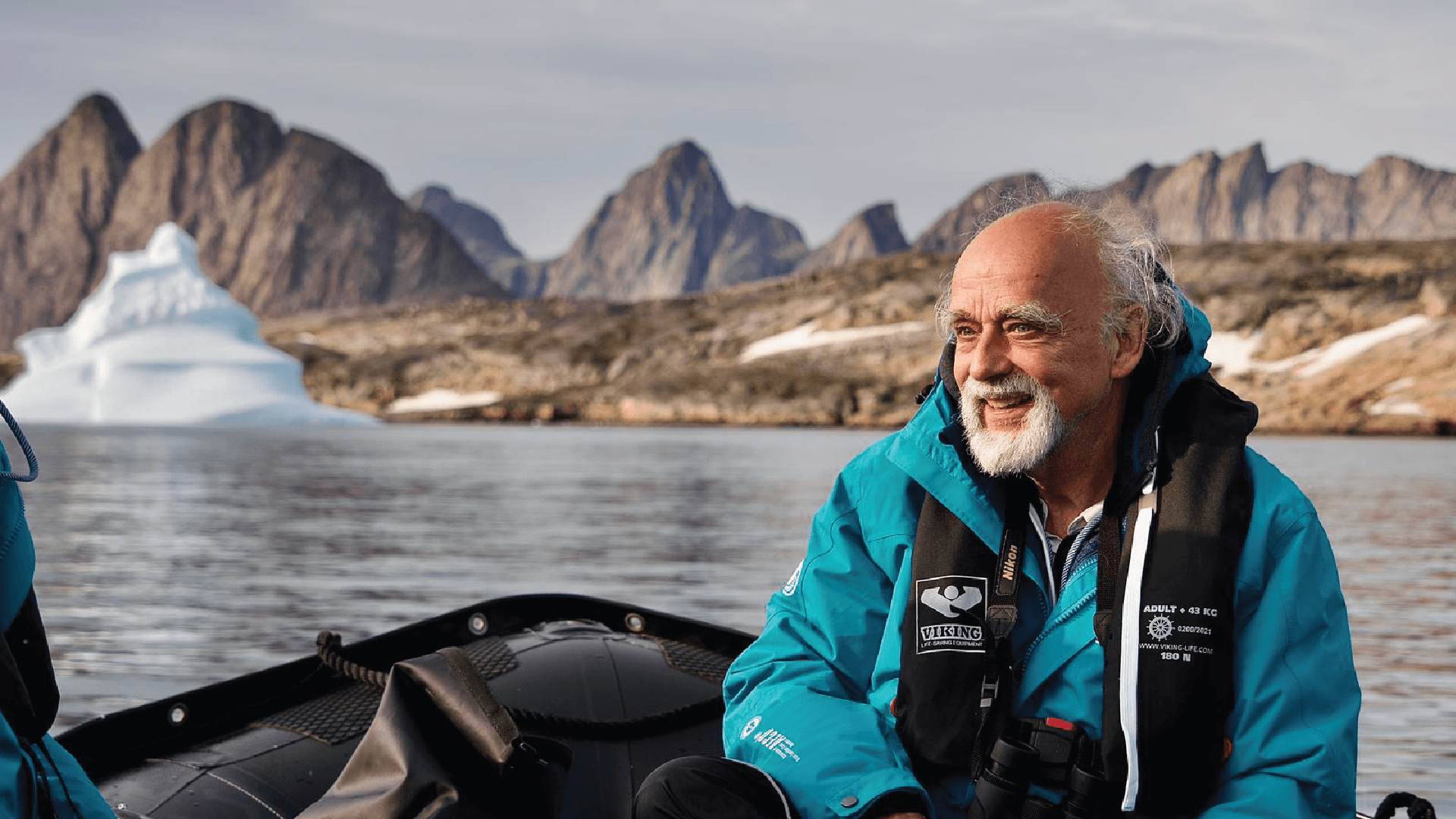

After decades of studying cooperative breeding in birds and the evolution of new frog species, and with a Ph.D. in biology, plus degrees in zoology, genetics and biochemistry, Uli Reyer now shares his knowledge aboard expedition cruises. His lectures blend deep scientific insight with accessible storytelling, inviting guests to see the polar world not just as a destination, but as a living system shaped by evolution, behavior and change, both natural and man-made.

"I didn’t just want to see nature – I wanted to understand why it’s that way."

"For a scientist like me, deserts are a paradise."

Hi Uli! What keeps drawing you back to the Arctic?

Uli: I’ve always been fascinated by deserts – hot sand and cold ice and snow deserts alike. They fascinate me because at first glance they look monotonous and lifeless, but on closer inspection you discover a fascinating diversity – subtle differences in geological formations, special adaptions of plants and animals, and sometimes even hidden remnants of a former human presence. For a scientist like me, deserts are a paradise. After many journeys into hot deserts – the Sahara, the Atacama, the Chinese Taklamakan, the Australian outback – I discovered the Arctic as my paradise a few years ago.

What first sparked your fascination with the natural world?

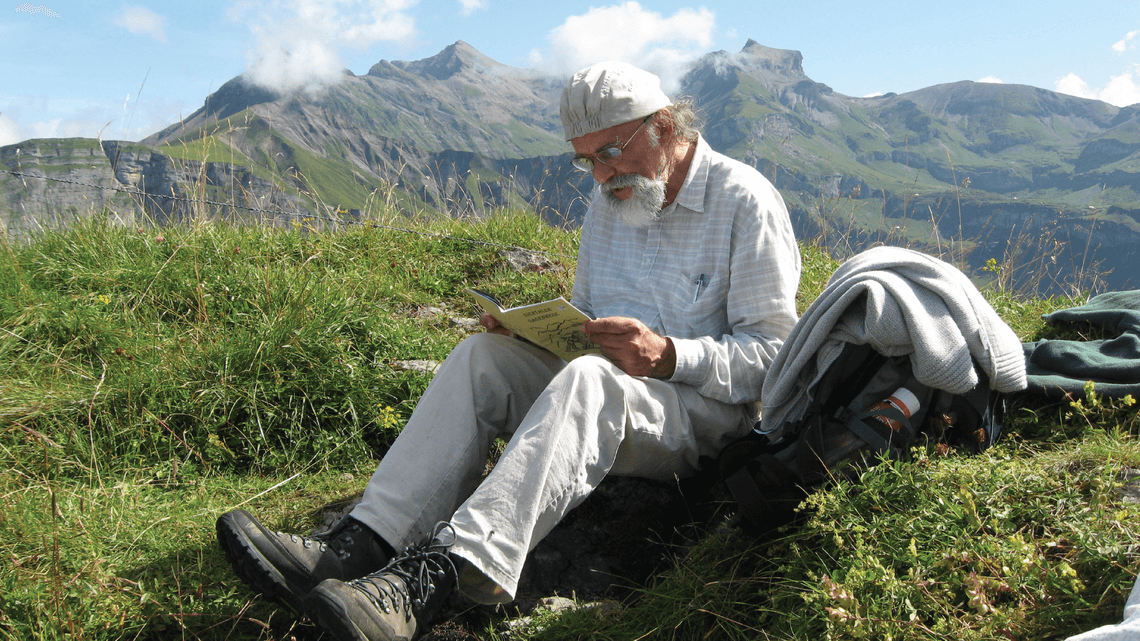

Uli: Nature has been part of my life from the beginning. I grew up on a farm near Hamburg, and spent time hiking and bird watching in the countryside with my family. I also had inspiring biology teachers at school. That early exposure stayed with me and shaped my choice to study biology.

How did your work on cooperative breeding evolve, and how did places like Kenya and Australia influence you?

Uli: I tried out many biological fields during my studies – from marine biology to bird observatories – before choosing the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology. It was a centre for behavioral ecology, looking at animal behavior as evolutionary adaptation. The approach requires fieldwork, which suited me perfectly. I stayed for many years, running a long-term study in Kenya and a shorter one in Australia. These experiences convinced me that understanding behavior means studying animals in their natural environments. As a result, all the projects that I initiated and supervised after my appointment at the University of Zurich were also characterized by a close link between behavior and the environment.

Why is it so important to link behavior, genetics, ecology and evolution?

Uli: What we see in animals and plants today – whether in the Arctic, the tropics, on land or in the ocean – is shaped by evolution: genetic variation filtered by natural selection. To truly understand a species, you have to study all those layers. This means that what we observe today can only be fully understood if we also know the past. It’s not just academic. Conservation, animal breeding, and other applied fields also depend on knowing how species function and where the limits of adaptation lie due to genetic makeup and evolutionary development and constraints.

Bridging worlds with words

Why is it important to you to bring science beyond the lab and into everyday life?

Uli: Science should benefit humanity in one way or another. Sometimes, as in medicine, that seems clear. In the basic sciences, which includes the type of research I’ve conducted, there’s also the possibility that some of the findings may be applied later on (e.g. to nature conservation), but the primary goal is to understand the fundamental laws and relationships in nature. People are curious – they read popular science books and watch documentaries. I see public outreach as cultural enrichment, like opera or theatre. It may not be “useful” in the narrow sense, but it enriches our lives.

Is travel a natural extension of your scientific mindset?

Uli: Actually, I think it's the other way around. It was the walks and family holidays that first sparked my curiosity – I didn't just want to see that nature is the way it is, I wanted to understand why it’s that way. And that curiosity has never stopped. It’s the driving force that made me a scientist, and it’s what has led me to be a guest lecturer on expedition cruises. These trips allow me to see new places, and share ideas with fellow travelers, and be curious.

How do you prepare for a voyage? Do you adapt to different audiences?

Uli: My aim is always the same: to make people say, “That was interesting, informative and entertaining.” Of course, I adjust depending on the audience. Guests on cruises need a different approach than biology students. But since I have decades of experience in both areas, it’s not difficult for me to choose the appropriate style. My lectures are tailored to the region – for instance, I talk about reindeer in Svalbard or musk oxen in Greenland when explaining Arctic ecosystems.

You’re known for myth-busting. What’s a common Arctic misconception?

Uli: Swan Hellenic calls it myth-busting because of my book on legendary creatures, like unicorns and dragons. But in the Arctic, one common misconception is that it's still pristine and untouched. That’s no longer true. Climate change, pollution, invasive species and overtourism are real threats. I use my lectures to address these changes – and the role we play in them.

Clarity in wild places

Are there polar animals that still surprise you?

Uli: The cold desert landscape itself fascinates me because it allows for surprising discoveries and insights time and again. But yes, I’m still fascinated by certain species: polar bears, musk oxen, arctic foxes, whales, and walruses. Also, the world of seabirds – they really bring the landscape to life during the summer breeding season.

How do you make complex science accessible on board?

Uli: I always begin with something familiar – a shared experience or a common observation. From there, I explain this detail in a broader context, for example with a basic biological law from the field of physiology or ecology. Then I build bridges to relevant findings from other disciplines such as behavioral research, genetics and evolution. I also use visuals – pictures, videos, animations – and mix in humor and interaction. That keeps things engaging, even for those new to the subject.

Do expedition cruises raise awareness of climate change and conservation?

Uli: Yes, these trips undoubtedly have the potential to raise awareness. As the saying goes, “You only protect what you know and love.” On my cruises, guests often tell me they hadn’t thought much about conservation before. After hearing the lectures and seeing the environment firsthand, they want to make changes. Not everyone will act, but if some do – and perhaps inspire others to rethink their attitudes and actions – then the voyage will have a lasting impact.

You’ll be speaking in English this time – does language affect your teaching style?

Uli: On this trip, everything will be exclusively in English, as that’s the language used on board Swan Hellenic ships. But I’m always available to German-speaking guests in informal settings – during shore excursions, meals, and at other times. For me, switching between languages doesn’t change the way I teach because I’ve communicated in both languages for years as a university professor in Zurich.

Traveling minds, changing worlds

What topics are you excited to highlight?

Uli: Among the topics that I’ll highlight are how the Arctic ecosystems differ from those further south – dramatic seasonal shifts, and unique fauna in places like Svalbard, Iceland and Greenland. These topics help explain how species adapt to their environment and where their limits lie. I also talk about climate change in a lecture called “The Polar Bear – An Icon of Climate Change.” In it, I also challenge extreme, one-sided views and urge people to focus on facts over emotion.

What do you hope Swan Hellenic guests will take away from your time together?

Uli: An appreciation for the beauty of the areas visited, and the fascinating variety of plants and animals found there. A better knowledge and understanding of ecosystems in general, and of Arctic ecosystems in particular. And an awareness of environmental vulnerability and the need for urgent and immediate protection.

What keeps you inspired after a lifetime in science?

Uli: As a scientist, you don't give up your curiosity when you retire. I still want to learn, explore, and ask questions. Every voyage brings something new – even in places I’ve been before, like Svalbard. I also learn from guests and colleagues. Some raise ideas I’ve never considered. Others know far more about these regions than I do. That’s what keeps it exciting!